Movie From the Early 60's That Follows a Family After La Has Been Bombed

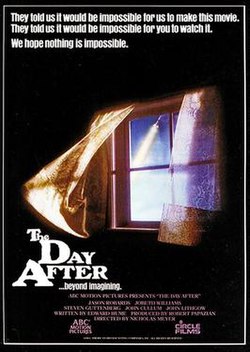

| The Mean solar day Subsequently | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Drama |

| Written by | Edward Hume |

| Directed by | Nicholas Meyer |

| Starring | Jason Robards JoBeth Williams Steve Guttenberg John Cullum John Lithgow Amy Madigan |

| Theme music composer | David Raksin Virgil Thomson (Theme for "The River") |

| Land of origin | United States |

| Original language | English |

| Production | |

| Producers | Robert Papazian (producer) Stephanie Austin (associate producer) |

| Cinematography | Gayne Rescher |

| Editors | William Paul Dornisch Robert Florio |

| Running time | 126 minutes |

| Production company | ABC Circle Films |

| Distributor | ABC Motion Pictures Disney–ABC Domestic Television |

| Release | |

| Original network | ABC |

| Picture format | Colour (CFI) |

| Sound format | Mono |

| Original release |

|

The Twenty-four hour period After is an American television set film that offset aired on November twenty, 1983, on the ABC television network. More 100 million people, in nearly 39 million households, watched the plan during its initial circulate.[ane] [2] [iii] With a 46 rating and a 62% share of the viewing audience during its initial broadcast, it was the seventh-highest-rated non-sports bear witness upwards to that time and set a record equally the highest-rated tv set film in history—a record information technology held equally of 2009.[3]

The film postulates a fictional state of war between the NATO forces and the Warsaw Pact countries that rapidly escalates into a full-calibration nuclear substitution between the United states and the Soviet Spousal relationship. The action itself focuses on the residents of Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas Urban center, Missouri, and of several family farms virtually nuclear missile silos.[4]

The cast includes JoBeth Williams, Steve Guttenberg, John Cullum, Jason Robards, and John Lithgow. The film was written by Edward Hume, produced by Robert Papazian, and directed past Nicholas Meyer. It was released on DVD on May 18, 2004, by MGM.

The pic was circulate on the Soviet Matrimony'due south land Tv in 1987,[5] in the menstruum of the negotiations on Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. The producers demanded that the Russian translation arrange to the original script and that the broadcast would not be interrupted by commentary.[6]

Plot [edit]

Military machine tensions rise between the two Common cold State of war powers led by the Soviet Union and the United States. Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact forces build on the border between Due east Germany and Westward Germany, and West Berlin is blockaded. A NATO endeavor to break the blockade results in heavy casualties. Airman Get-go Form Billy McCoy (William Allen Immature) lives at Whiteman Air Force Base near Sedalia, Missouri. He is called to alert status at the Minuteman launch site he is stationed at in Sweetsage, Missouri, twenty miles (32 km) from Kansas City. The Hendry family lives on a farm adjoining McCoy'southward launch site.

The Dahlberg family lives on their farm twenty miles (32 km) away from the Sweetsage launch site, in Harrisonville, Missouri, forty miles (64 km) from Kansas Metropolis. The Dahlbergs' eldest daughter Denise (Lori Lethin) is set to be married in 2 days to a student at the University of Kansas, and they perform their wedding ceremony dress rehearsal.

The next day, the military disharmonize in Europe quickly escalates. Tactical nuclear weapons are detonated by NATO to finish a Soviet Marriage advance into West Deutschland, and each side attacks naval targets in the Farsi Gulf. Dr. Russell Oakes (Jason Robards), a dr. in Kansas City, Missouri, travels to Lawrence, Kansas, by car to teach a grade at the University of Kansas hospital there. Pre-med University of Kansas student Stephen Klein (Steve Guttenberg) receives a physical at the infirmary, hears the news from Europe, and decides to hitchhike toward home in Joplin, Missouri.

As the threat of big-scale nuclear attack grows, hoarding begins, and so does evacuation of major cities in both the Soviet Union and United States. Frequent Emergency Broadcast System warnings are sent over television and radio, and Kansas City begins to empty, clogging outbound freeways. Dr. Oakes is among the many stuck in the traffic jam as he drives toward Lawrence, but, after hearing an EBS alert and realizing the danger to Kansas City and his family living there, decides to turn around and head home.

Minutes apart, the U.s. launches its Minuteman missiles, and United States military personnel aboard the EC-135 Looking Glass shipping track entering Soviet nuclear missiles. The moving-picture show deliberately leaves unclear who fired theirs first. Billy McCoy flees the site he was stationed at at present that its Minuteman missile has been launched, intending to locate his married woman and kid. As air raid sirens go off, widespread panic grips Kansas City as almost people aimlessly seek fallout shelters and other protection from the imminent Soviet nuclear attack.

A high-altitude nuclear explosion occurs over the primal Usa, generating an electromagnetic pulse which disables vehicles and destroys the electrical grid. Before long thereafter, high-yield nuclear weapons detonate over numerous locations, including downtown Kansas Urban center, Sedalia, and Sweetsage. The Hendry family unit, having initially ignored the crisis, is killed when they try to flee. McCoy takes refuge in a truck trailer, and Klein, who had hitchhiked every bit far as Harrisonville, finds the Dahlberg home and begs for protection in the family's basement. In the concurrently, young Danny Dahlberg is wink blinded upon looking at a nearby nuclear detonation. Dr. Oakes, who witnessed the nuclear explosion over Kansas Urban center, walks to the hospital in Lawrence and begins treating patients.

Nuclear fallout and its deadly effects are felt everywhere in the region. McCoy and Oakes, both outside immediately afterward the explosions, accept been exposed without their knowledge to lethal doses of radiations. Denise Dahlberg, frantic later on days in the family's basement shelter, runs outside, and Klein, who vows to her father that he'll bring her back, does so, but not before both have been exposed to very loftier doses of radiations. McCoy learns in his travels that Sedalia and many other cities have been obliterated. Food and h2o are in very short supply, and annexation and other criminal activity leads to the imposition of martial police. Klein takes Denise and her blood brother Danny, who was blinded past 1 of the nuclear explosions, to the hospital in Lawrence for handling. McCoy also travels there, where he dies of radiation poisoning. Denise and Danny Dahlberg, and Klein, finally go out for Harrisonville and the Dahlberg farm, when it becomes clear to them they cannot be treated medically for their injuries; information technology is implied that Denise and Klein'due south conditions are terminal.

Jim Dahlberg, returning dwelling house from a municipal meeting virtually agricultural techniques that may work to grow food in the new circumstances, finds squatters on the farm. He explains that information technology is his country, and asks them to leave, at which point one of the squatters shoots and kills him without whatsoever sign of remorse.

Dr. Oakes, at concluding aware he has sustained lethal exposure to radiations, returns to Kansas City on pes to see the site of his habitation before he dies. He finds squatters there, attempts to drive them off, and is instead offered food. Oakes collapses, weeps, and one of the squatters comforts him.

The flick ends every bit Lawrence science faculty head Joe Huxley repeatedly tries to contact other survivors with a shortwave radio. In that location is no response.

Cast [edit]

Product [edit]

The Solar day Afterward was the idea of ABC Motion Movie Segmentation president Brandon Stoddard,[vii] who, after watching The Prc Syndrome, was then impressed that he envisioned creating a picture show exploring the effects of nuclear war on the Usa. Stoddard asked his executive vice president of telly movies and miniseries Stu Samuels to develop a script. Samuels created the title The Day After to emphasize that the story was not about a nuclear war itself, only the backwash. Samuels suggested several writers and somewhen Stoddard deputed veteran television writer Edward Hume to write the script in 1981. ABC, which financed the production, was concerned virtually the graphic nature of the film and how to accordingly portray the subject on a family unit-oriented television aqueduct. Hume undertook a massive corporeality of research on nuclear war and went through several drafts until finally ABC deemed the plot and characters acceptable.

Originally, the film was based more around and in Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City was non bombed in the original script, although Whiteman Air Force Base was, making Kansas Metropolis suffer shock waves and the horde of survivors staggering into town. At that place was no Lawrence, Kansas in the story, although there was a minor Kansas boondocks called "Hampton". While Hume was writing the script, he and producer Robert Papazian, who had cracking feel in on-location shooting, took several trips to Kansas City to scout locations and met with officials from the Kansas picture show commission and from the Kansas tourist offices to search for a suitable location for "Hampton." It came downwardly to a choice of either Warrensburg, Missouri, and Lawrence, Kansas, both college towns—Warrensburg was home of Central Missouri Land University and was well-nigh Whiteman Air Force Base of operations and Lawrence was home of the University of Kansas and was near Kansas City. Hume and Papazian concluded upwardly selecting Lawrence, due to the access to a number of good locations: a university, a hospital, football and basketball venues, farms, and a apartment countryside. Lawrence was also agreed upon as being the "geographic center" of the U.s.a.. The Lawrence people were urging ABC to change the proper noun "Hampton" to "Lawrence" in the script.

Back in Los Angeles, the idea of making a Television set pic showing the true furnishings of nuclear state of war on average American citizens was nonetheless stirring up controversy. ABC, Hume, and Papazian realized that for the scene depicting the nuclear nail, they would take to utilize country-of-the-art special effects and they took the first step past hiring some of the best special effects people in the business to draw up some storyboards for the complicated blast scene. Then, ABC hired Robert Butler to directly the projection. For several months, this group worked on drawing upwardly storyboards and revising the script again and once more; and then, in early 1982, Butler was forced to leave The Day Subsequently because of other contractual commitments. ABC then offered the projection to 2 other directors, who both turned information technology down. Finally, in May, ABC hired feature motion-picture show director Nicholas Meyer, who had just completed the blockbuster Star Trek Ii: The Wrath of Khan. Meyer was apprehensive at first and doubted ABC would go away with making a television film on nuclear war without the censors diminishing its effect. However, after reading the script, Meyer agreed to direct The Day Later on.

Meyer wanted to make sure he would picture the script he was offered. He did not desire the censors to censor the picture, nor the film to be a regular Hollywood disaster moving picture from the start. Meyer figured the more The Day After resembled such a film, the less effective it would exist, and preferred to present the facts of nuclear war to viewers. He made it articulate to ABC that no big TV or film stars should be in The 24-hour interval After. ABC agreed, although they wanted to accept i star to assistance attract European audiences to the film when information technology would be shown theatrically at that place. Later on, while flying to visit his parents in New York City, Meyer happened to exist on the aforementioned plane with Jason Robards and asked him to bring together the cast.

Meyer plunged into several months of nuclear research, which made him quite pessimistic about the future, to the point of condign ill each evening when he came domicile from work. Meyer and Papazian also made trips to the ABC censors, and to the United States Section of Defense during their research stage, and experienced conflicts with both. Meyer had many heated arguments over elements in the script that the network censors wanted cut out of the pic. The Department of Defense said they would cooperate with ABC if the script made clear that the Soviet Union launched their missiles first—something Meyer and Papazian took pains not to do.

Meyer, Papazian, Hume, and several casting directors spent nearly of July 1982 taking numerous trips to Kansas Metropolis. In between casting in Los Angeles, where they relied mostly on unknowns, they would fly to the Kansas City surface area to interview local actors and scenery. They were hoping to find some existent Midwesterners for smaller roles. Hollywood casting directors strolled through shopping malls in Kansas City, looking for local people to fill small-scale and supporting roles, while the daily newspaper in Lawrence ran an advertisement calling for local residents of all ages to sign up for jobs as a large number of extras in the film and a professor of theater and movie at the University of Kansas was hired to caput up the local casting of the motion picture. Out of the eighty or so speaking parts, but fifteen were cast in Los Angeles. The remaining roles were filled in Kansas City and Lawrence.

While in Kansas City, Meyer and Papazian toured the Federal Emergency Management Agency offices in Kansas City. When asked what their plans for surviving nuclear war were, a FEMA official replied that they were experimenting with putting evacuation instructions in phone books in New England. "In nigh vi years, everyone should have them." This coming together led Meyer to later refer to FEMA as "a consummate joke." It was during this time that the conclusion was fabricated to change "Hampton" in the script to "Lawrence." Meyer and Hume figured since Lawrence was a real town, that it would exist more believable and besides, Lawrence was a perfect choice to play a representative of Middle America. The town boasted a "socio-cultural mix," sat near the exact geographic center of the continental U.South., and Hume and Meyer'south enquiry told them that Lawrence was a prime missile target, considering 150 Minuteman missile silos stood nearby. Lawrence had some bang-up locations, and the people at that place were more supportive of the projection. Suddenly, less emphasis was put on Kansas City, the decision was made to have the urban center completely annihilated in the script, and Lawrence was made the master location in the film.

Editing [edit]

ABC originally planned to air The Day Subsequently as a iv-hour "goggle box upshot", spread over two nights with total running fourth dimension of 180 minutes without commercials.[8] Managing director Nicholas Meyer felt the original script was padded, and suggested cutting out an hr of cloth to present the whole moving picture in one night. The network stuck with their two night broadcast program, and Meyer filmed the unabridged three-hour script, as evidenced by a 172-infinitesimal work-print that has surfaced.[9] After, the network found that it was difficult to find advertisers, considering the subject affair. ABC relented, and told Meyer he could edit the film for a one-night broadcast version. Meyer's original single-night cutting ran two hours and twenty minutes, which he presented to the network. Later this screening, many executives were deeply moved and some even cried, leading Meyer to believe they approved of his cutting.

Nevertheless, a further half dozen-month struggle ensued over the concluding shape of the film. Network censors had opinions about the inclusion of specific scenes, and ABC itself, eventually intent on "trimming the pic to the os", made demands to cut out many scenes Meyer strongly lobbied to go on. Finally Meyer and his editor Bill Dornisch balked. Dornisch was fired, and Meyer walked away from the project. ABC brought in other editors, but the network ultimately was non happy with the results they produced. They finally brought Meyer back and reached a compromise, with Meyer paring downwards The Twenty-four hours After to a final running time of 120 minutes.[10] [11]

Broadcast [edit]

The Twenty-four hours Later on was initially scheduled to premiere on ABC in May 1983, but the mail service-production work to reduce the motion-picture show'due south length pushed back its initial airdate to November. Censors forced ABC to cut an entire scene of a kid having a nightmare well-nigh nuclear holocaust and then sitting up, screaming. A psychiatrist told ABC that this would disturb children. "This strikes me every bit ludicrous," Meyer wrote in TV Guide at the time, "not only in relation to the residue of the motion picture, but also when contrasted with the huge doses of violence to be found on whatsoever boilerplate evening of TV viewing." In whatsoever case, they made a few more cuts, including to a scene where Denise possesses a diaphragm. Another scene, where a hospital patient abruptly sits up screaming, was excised from the original television broadcast but restored for habitation video releases. Meyer persuaded ABC to dedicate the film to the citizens of Lawrence, and also to put a disclaimer at the end of the film, following the credits, letting the viewer know that The Day Afterward downplayed the true effects of nuclear war so they would be able to have a story. The disclaimer also included a list of books that provide more information on the subject.

The Day After received a large promotional campaign prior to its broadcast. Commercials aired several months in accelerate, ABC distributed half a million "viewer's guides" that discussed the dangers of nuclear war and prepared the viewer for the graphic scenes of mushroom clouds and radiation burn down victims. Give-and-take groups were also formed nationwide.[12]

Music [edit]

Composer David Raksin wrote original music and adapted music from The River (a documentary picture show score by concert composer Virgil Thomson), featuring an adaptation of the hymn "How Firm a Foundation". Although he recorded just under 30 minutes of music, much of it was edited out of the final cutting. Music from the Commencement Strike footage, conversely, was not edited out.

Deleted and alternative scenes [edit]

Due to the film'south being shortened from the original three hours (running fourth dimension) to two, several planned special-furnishings scenes were scrapped, although storyboards were fabricated in anticipation of a possible "expanded" version. They included a "bird'due south eye" view of Kansas City at the moment of two nuclear detonations as seen from a Boeing 737 airliner on approach to the urban center'southward airport, as well as simulated newsreel footage of U.South. troops in West Germany taking up positions in preparation of advancing Soviet armored units, and the tactical nuclear exchange in Germany between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, which follows after the attacking Warsaw Pact force breaks through and overwhelms the NATO lines.

ABC censors severely toned down scenes to reduce the torso count or severe burn victims. Meyer refused to remove central scenes just reportedly some viii and a one-half minutes of excised footage still exist, significantly more than graphic. Some footage was reinstated for the film'south release on home video. Additionally, the nuclear attack scene was longer and supposed to feature very graphic and very accurate shots of what happens to a human torso during a nuclear blast. Examples included people being set on fire, their mankind carbonizing, existence burned to the bone, eyes melting, faceless heads, skin hanging, deaths from flying glass and debris, limbs torn off, beingness crushed, blown from buildings past the shockwave, and people in fallout shelters suffocating during the firestorm. As well cut were images of radiation sickness, as well as graphic post-attack violence from survivors such as food riots, looting, and general lawlessness as government attempted to restore guild.

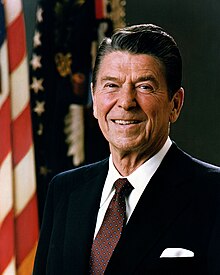

Ane cut scene shows surviving students battling over food. The two sides were to be athletes versus the science students under the guidance of Professor Huxley. Some other brief scene later cutting related to a firing squad, where ii U.S. soldiers are blindfolded and executed. In this scene, an officer reads the charges, verdict and sentence, as a bandaged chaplain reads the Concluding Rites.[ citation needed ] A like sequence occurs in a 1965 UK-produced faux documentary, The State of war Game. In the initial 1983 broadcast of The Day Later, when the U.Southward. president addresses the nation, the vox was an imitation of and so-President Ronald Reagan (who later stated that he watched the film and was deeply moved).[13] In subsequent broadcasts, that voice was overdubbed by a stock actor.

Habitation video releases in the U.S. and internationally come in at various running times, many listed at 126 or 127 minutes; full screen (iv:3 aspect ratio) seems to be more than common than widescreen. RCA videodiscs of the early on 1980s were express to ii hours per disc, so that full screen release appears to be closest to what originally aired on ABC in the US. A 2001 U.Southward. VHS version (Anchor Bay Entertainment, Troy, Michigan) lists a running time of 122 minutes. A 1995 double laser disc "director's cut" version (Image Entertainment) runs 127 minutes, includes commentary by director Nicholas Meyer and is "presented in its 1.75:1 European theatrical aspect ratio" (co-ordinate to the LD jacket).

Ii different German DVD releases run 122 and 115 minutes; edits reportedly downplay the Soviet Matrimony's function.[14]

A two disc Blu-ray special edition[15] was released in 2018 by video specialty characterization Kino Lorber, presenting the film in loftier definition. The release contains both the 122-infinitesimal television cutting, presented in a 4:iii aspect ratio as broadcast, also equally the 127-minute theatrical cut presented in a 16:9 widescreen attribute ratio.

Reception [edit]

On its original broadcast (Sunday, November 20, 1983), John Cullum warned viewers before the motion picture was premiered that the film contains graphic and agonizing scenes, and encouraged parents who have young children watching, to watch together and discuss the bug of nuclear warfare.[16] ABC and local TV affiliates opened i-800 hotlines with counselors standing by. At that place were no commercial breaks later on the nuclear attack. ABC then aired a live debate on Viewpoint, ABC's occasional discussion plan hosted by Nightline 'due south Ted Koppel, featuring scientist Carl Sagan, former Secretarial assistant of State Henry Kissinger, Elie Wiesel, sometime Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, General Brent Scowcroft and commentator William F. Buckley Jr.. Sagan argued confronting nuclear proliferation, while Buckley promoted the concept of nuclear deterrence. Sagan described the artillery race in the following terms: "Imagine a room brimful in gasoline, and at that place are 2 implacable enemies in that room. One of them has ix k matches, the other seven g matches. Each of them is concerned near who's ahead, who's stronger."[17]

The moving picture and its subject matter were prominently featured in the news media both earlier and later the broadcast, including on such covers equally Time,[eighteen] Newsweek,[19] U.Southward. News & World Report, [xx] and Telly Guide. [21]

Critics tended to claim the motion picture was either sensationalizing nuclear war or that information technology was too tame.[22] The special furnishings and realistic portrayal of nuclear war received praise. The film received 12 Emmy nominations and won 2 Emmy awards. It was rated "way above boilerplate" in Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide, until all reviews for movies sectional to Television set were removed from the publication.[23]

In the The states, 38.5 million households, or an estimated 100 million people, watched The Day After on its first circulate, a record audience for a made-for-Boob tube motion-picture show.[24] Producers Sales Arrangement released the film theatrically effectually the globe, in the Eastern Bloc, China, North korea and Republic of cuba (this international version contained six minutes of footage not in the telecast edition). Since commercials are not sold in these markets, Producers Sales Organization failed to gain acquirement to the tune of an undisclosed sum.[ citation needed ] Years afterwards this international version was released to tape by Embassy Dwelling Entertainment.

Actor and former Nixon adviser Ben Stein, critical of the film's bulletin (i.eastward. that the strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction would atomic number 82 to a war), wrote in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner what life might be like in an America under Soviet occupation. Stein'due south idea was eventually dramatized in the miniseries Amerika, also broadcast by ABC.[25]

The New York Post accused Meyer of being a traitor, writing, "Why is Nicholas Meyer doing Yuri Andropov's work for him?" Much press comment focused on the unanswered question in the motion picture of who started the war.[26] Richard Grenier in the National Review accused The Twenty-four hours After of promoting "unpatriotic" and pro-Soviet attitudes.[27]

Television critic Matt Zoller Seitz in his 2016 book co-written with Alan Sepinwall titled TV (The Book) named The Day Later on as the fourth greatest American Tv-movie of all time, writing: "Very perchance the bleakest TV-moving picture ever broadcast, The Mean solar day After is an explicitly antiwar statement dedicated entirely to showing audiences what would happen if nuclear weapons were used on noncombatant populations in the United States."[28]

Furnishings on policymakers [edit]

After seeing the pic, Ronald Reagan wrote that the movie was very effective and left him depressed.

U.Southward. President Ronald Reagan watched the motion-picture show more than a month earlier its screening, on Columbus Day, Oct 10, 1983.[29] He wrote in his diary that the film was "very effective and left me greatly depressed,"[30] [26] and that information technology changed his listen on the prevailing policy on a "nuclear state of war".[31] The film was also screened for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A authorities advisor who attended the screening, a friend of Meyer's, told him "If you wanted to describe blood, you did it. Those guys sabbatum there similar they were turned to stone."[ citation needed ] In 1987, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which resulted in the banning and reducing of their nuclear armory. In Reagan'due south memoirs, he drew a straight line from the movie to the signing.[26] Reagan supposedly later sent Meyer a telegram after the summit, maxim, "Don't retrieve your movie didn't have whatsoever function of this, because information technology did."[10] However, during an interview in 2010, Meyer said that this telegram was a myth, and that the sentiment stemmed from a friend's letter to Meyer; he suggested the story had origins in editing notes received from the White House during the production, which "...may have been a joke, merely it wouldn't surprise me, him beingness an old Hollywood guy."[26]

The film also had touch outside the U.S. In 1987, during the era of Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika reforms, the film was shown on Soviet television. Four years before, Georgia Rep. Elliott Levitas and 91 co-sponsors introduced a resolution in the U.S. House of Representatives "[expressing] the sense of the Congress that the American Broadcasting Company, the Department of State, and the U.S. Information Bureau should piece of work to have the television film The Day Subsequently aired to the Soviet public."[32]

Accolades [edit]

The Day Later on won two Emmy Awards and received 10 other Emmy nominations.[33]

Emmy Awards won:

- Outstanding Motion-picture show Sound Editing for a Limited Series or a Special

- Outstanding Accomplishment in Special Visual Furnishings

Emmy Honour nominations:

- Outstanding Achievement in Hairstyling

- Outstanding Accomplishment in Makeup

- Outstanding Art Direction for a Limited Series or a Special (Peter Wooley)

- Outstanding Cinematography for a Express Series or a Special (Gayne Rescher)

- Outstanding Directing in a Limited Series or a Special (Nicholas Meyer)

- Outstanding Drama/One-act Special (Robert Papazian)

- Outstanding Moving-picture show Editing for a Limited Series or a Special (William Dornisch and Robert Florio)

- Outstanding Pic Sound Mixing for a Express Serial or a Special

- Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Limited Serial or a Special (John Lithgow)

- Outstanding Writing in a Express Series or a Special (Edward Hume)

See besides [edit]

- Tv set Event, a documentary film about the making and release of the film

- Attestation, a television moving picture moved to theatrical release two weeks before The Twenty-four hours After aired

- Threads, a British television film that centres on a nuclear state of war and the societal later on-effects

- List of nuclear holocaust fiction

- Nuclear weapons in popular culture

References [edit]

- ^ Poniewozik, James (September vi, 2007). "ALL-Time 100 TV Shows: The Day After". Time. Archived from the original on Oct 25, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "Tipoff". The Ledger. Jan twenty, 1989. Retrieved October eleven, 2011.

- ^ a b "Pinnacle 100 Rated TV Shows Of All Time". Screener. Tribune Media Services. March 21, 2009. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "The Day After - 25 November 1983". BBC. Retrieved September xviii, 2016.

- ^ "«На следующий день» (The Mean solar day Later, 1983)". КиноПоиск . Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Soviet Spousal relationship to air ABC's 'The Day After'".

- ^ Weber, Bruce (December 23, 2014). "Brandon Stoddard, 77, ABC Executive Who Brought 'Roots' to Telly, Is Dead". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Naha, Ed (April 1983). "50.A. Offbeat: A Lesson in Reality". Starlog: 24–25.

- ^ nisus8 (August 10, 2018), The Mean solar day After (1983) - three-Hour Workprint Version, archived from the original on September eleven, 2018, retrieved May 23, 2019

- ^ a b Niccum, John (November nineteen, 2003). "Fallout from The Mean solar day Afterwards". lawrence.com . Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Meyer, Nicholas, "The View From the Span: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood", folio 150. Viking Developed, 2009

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (November 22, 1983). "Atomic State of war Film Spurs Nationwide Discussion". The New York Times.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "The Twenty-four hour period Later: "Reagan-esque" Presidential Address". YouTube.

- ^ Motion-picture show-censorship.com

- ^ "The Solar day After (two-Disc Special Edition)".

- ^ 11/20/1983 The Day Later on Intro and Disclaimer ABC - via YouTube

- ^ Allyn, Bruce (September nineteen, 2012). The Edge of Armageddon: Lessons from the Brink. RosettaBooks. p. x. ISBN978-0-7953-3073-5.

- ^ Fourth dimension

- ^ Backissues.com

- ^ Backissues.com

- ^ Backissues.com

- ^ Emmanuel, Susan. "The Day After". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Archived from the original on January xvi, 2013.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard. Leonard Maltin's Boob tube Movies And Video Guide 1987 edition. Signet. p. 218.

- ^ Stuever, Hank (May 12, 2016). "Yes, 'The Solar day Later on' really was the profound TV moment 'The Americans' makes it out to be". Washington Post – Blogs . Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ The New York Times: "TV VIEW; 'AMERKIA' (sic) – SLOGGING THROUGH A MUDDLE" By John J. O'Connor. Published February fifteen, 1987

- ^ a b c d Empire, "How Ronald Reagan Learned To Kickoff Worrying And Stop Loving The Bomb", November 2010, pp 134–140

- ^ Grenier, Richard. "The Brandon Stoddard Horror Show." National Review (1983): 1552–1554.

- ^ Sepinwall, Alan; Seitz, Matt Zoller (September 2016). TV (The Book): 2 Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time (1st ed.). New York, NY: Grand Fundamental Publishing. p. 372. ISBN9781455588190.

- ^ Stover, Dawn. "Facing nuclear reality, 35 years subsequently The Day After". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists . Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ "Diary Entry - x/10/1983 | The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute". www.reaganfoundation.org . Retrieved September x, 2019.

- ^ Reagan, An American Life, 585

- ^ "thomas.loc.gov, 98th Congress (1983–1984), H.CON.RES.229"

- ^ "The Twenty-four hours After An ABC Theatre Presentation". Television University . Retrieved January xiii, 2019.

Further reading [edit]

- Cheers, Michael, "Search for Television Stars Not Yielding Right Types", Kansas City Times, July nineteen, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "Moviemakers Cast About for Local Crowds", Lawrence Periodical-Globe, August 16, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "Simulated Farmstead Goes Up in Flames for Moving-picture show", Lawrence Journal-World, August 17, 1982.

- Laird, Linda, "The Days Earlier 'The Solar day Later'", Midway, the Sunday Mag Department of the Topeka Upper-case letter-Journal, August 22, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "Shooting on Schedule '24-hour interval Afterwards' Picture show", Lawrence Journal-World, August 23, 1982.

- Lazzarino, Evie, "From Production Coiffure to Extras, a Day in the Life of 'Day Afterward'", Lawrence Journal-Earth, August 29, 1982.

- Rosenberg, Howard, "'Humanizing' Nuclear Devastation in Kansas", Los Angeles Times, September 1, 1982.

- Schrenier, Bruce, "'The Twenty-four hour period After' Filming Continues at KU", Academy Daily Kansan, September ii, 1982.

- Appelbaum, Sharon, "Lawrence Folks Are Dying for a Function in Tv'south Armageddon", The Kansas City Star, September 3, 1982.

- Hitchcock, Doug, "Moving-picture show Makeup Manufactures Medical Mess", Lawrence Periodical-World, September five, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "Nicholas Meyer Tackles Biggest Fantasy", Lawrence Journal-World, September 5, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "How to Spend $ane Million in Lawrence", Lawrence Journal-World, September 5, 1982.

- Twardy, Chuck, "Students Assume War-Torn Look as Moving picture Shooting Winds Downwards", Lawrence Journal-World, September 8, 1982.

- Goodman, Howard, "KC 'Holocaust' a Mix of Horror and Hollywood", Kansas Metropolis Times, September 11, 1982.

- Hashemite kingdom of jordan, Gerald B., "Local Filming of Nuclear Disaster Virtually Fizzles", The Kansas City Star, September 13, 1982.

- Kindall, James, "Apocalypse Now", The Kansas City Star Weekly Magazine, Oct 17, 1982.

- Loverock, Patricia, "ABC Films Nuclear Holocaust in Kansas", On Location magazine, November 1983.

- Bauman, Melissa, "ABC Official Denies Network Can't Find Sponsors for Show", Lawrence Periodical-World, November thirteen, 1983.

- Meyer, Nicholas, "'The Day Later': Bringing the Unwatchable to TV", Tv Guide, Nov 19, 1983.

- Torriero, E.A., "The Day Before 'The Day After'", Kansas City Times, Nov xx, 1983.

- Hoenk, Mary, "'Day After': Are Young Viewers Ready?", Lawrence Journal-World, Nov 20, 1983.

- Helliker, Kevin, "'Twenty-four hour period Afterward' Yields a Grim Evening", Kansas City Times, November 21, 1983.

- Trowbridge, Caroline and Hoenk, Mary, "Motion picture'due south Fallout: A Solemn Plea for Peace", Lawrence Journal-Globe, Nov 21, 1983.

- Greenberger, Robert, "Nicholas Meyer: Witness at the Stop of the World", Starlog magazine, January 1984.

- Eisenberg, Adam, "Waging a Four-Minute War", Cinefex mag, January 1984.

- Boyd-Bowman, Susan (1984). "The Day After: Representations of the Nuclear Holocaust". Screen. vi (4): 18–27.

- Meyer, Nicholas (1983). The Day After (Tv set-Miniseries). United States: Diplomatic mission Habitation Amusement.

- Perrine, Toni A., PhD (1991). "Beyond Apocalypse: Recent Representations of Nuclear War and its Aftermath in United states of america Narrative Pic". Final Draft. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links [edit]

- The 24-hour interval After at IMDb

- The 24-hour interval Subsequently at AllMovie

- The Day After at Rotten Tomatoes

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Day_After

0 Response to "Movie From the Early 60's That Follows a Family After La Has Been Bombed"

Post a Comment